Reification and Truthmaking Patterns

- http://www.inf.ufes.br/~gguizzardi/ER2018-Truthmaking.pdf

- keywords: Ontology-Driven Conceptual Modeling OntoUML DOLCE Unified Foundational Ontology

Abstract

- Reification is a standard technique in conceptual modeling, which consists of including in the domain of discourse entities that may otherwise be hidden or implicit. However, deciding what should be reified is not always easy. Recent work on formal ontology offers us a simple answer: put in the domain of discourse those entities that are responsible for the (alleged) truth of our propositions. These are called truthmakers. Re-visiting previous work, we propose in this paper a systematic analysis of truthmaking patterns for properties and relations based on the ontological nature of their truthmakers. Truthmaking patterns will be presented as generalization of reification patterns, accounting for the fact that, in some cases, we do not reify a property or a relationship directly, but we rather reify its truthmakers.

Highlights

- strong view: events

- weak view: qualities

Search for TMs

- our cognitive domain is much bigger than our domain of discourse

- e.g., when we say that John and Mary are married, our language only refers to them, although we know that there has been a wedding event and that there is an ongoing marriage relationship. It is up to us to introduce these further entities in our domain of discourse, should we need to represent and reason about them.

- Such process of making hidden entities explicit is called reification.

- Note that the new entities do not originate from a generic decision to expand the domain, but rather from a transformation of a language construct (typically, a predicate) into a domain element (a “first class citizen”).

- the basic questions we need to ask to analyze a proposition P are similar to the famous Wh-questions: What is responsible for making P true? When and Where will P be true?

Properties and Their Truthmakers

- only propositions have TMs (they are the only truthbearers) but we shall talk interchangeably of TMs of properties or relations (holding for certain entities), and TMs of propositions

- take e.g. "a is a rose" vs "a is red"

- Strong TM: "existence" (non-descriptive) and "a particular occurrence of redness, that is, a particular event (intended in the most general sense that includes states)" (descriptive)

- non-descriptive properties account for what something is, on the basis of its nature and structure; descriptive properties account for how something is, on the basis of its qualities.

- Weak TM makes a proposition true not just because of its existence (i.e., because of its essential nature), but because of the way it contingently is (i.e., because of its actual nature).

- e.g. Suppose that a is red at time t1, and becomes brown at time t2.

- According to the mainstream TM theory, the strong TM of a is brown at t2 will be very different from that of a is red at t1 (i.e., 2 strong TMs)

- Parsons: the weak TM at both times is the rose itself: since the rose changes while keeping its identity, it is the very same rose, in virtue of the way it (contingently) is at t1 and at t2 (i.e., 1 weak TM)

- e.g. Suppose that a is red at time t1, and becomes brown at time t2.

Individual qualities, descriptive properties, intrinsic properties

Individual qualities

- This color is modeled as an individual quality in DOLCE and in Unified Foundational Ontology.

- qualities inhere in things, where inherence is a special kind of existential dependence relation, which is irreflexive, asymmetric, anti-transitive and functional

- They are directly comparable, while objects and events can be compared only with respect to a certain quality kind (e.g., to compare physical objects, one resorts to the comparison of their shapes, sizes, weights, and so on

- Qualities are distinct from their values (a.k.a. qualia), which are abstract entities representing what exactly resembling qualities have in common, and are organized in spaces called quality spaces; each quality kind has its own quality space

- e.g. weight is a quality kind, whose qualia form a linear quality space

- t.2024.07.14.17 maybe quantitave weight;

- e.g. weight is a quality kind, whose qualia form a linear quality space

- quality spaces may have a complex structure with multiple dimensions, each corresponding to a simple quality that inheres in a complex quality.

- typical example: colors and taste

- but also mental entities such as attitudes, intentions and beliefs as complex qualities, collapsing, for the sake of simplicity, UFO’s distinction between qualities and modes

- t.2024.07.26.09 qualities are descriptive, so I guess intentions could be descriptive, but couldn't you say "having an intent is non-descriptive since it holds in virtue of the object that has the intent"

- relational qualities are existentially dependent on the thing they inhere in, but also something else, e.g. John's love for Mary

- typical come in bundles called relators

- summary: individual qualities are weak TMs for descriptive properties

- note: looking for qualities as minimal weak TMs has a clear advantage over looking for strong TMs: while negative truths are notoriously a problem for the strong truthmaking view, so that it is difficult to individuate the strong TM of a is not red, it is immediate to see that its minimal weak TM is its color, and not, say, its weight.

descriptive properties

- we may define them as properties holding in virtue of one or more inhering qualities

- seems plausible to assume that a descriptive property may hold for an object x in virtue of a quality inhering in a proper part of x, rather than in x itself

- So, having a big nose counts as descriptive since it holds in virtue of the nose’s size, while having a nose is non-descriptive since it holds in virtue of the object that has the nose, which is not a quality.

- we should account also for descriptive properties that hold in virtue of relational qualities.

- 3 possibilities:

tional quality inhering in John, as in the case of being in love with Mary;- the weak TM consists of just one rela-- the truthmaking qualities are distributed between John and an external entity. This is the case of being married with Mary, which presupposes the existence of commitments and obligations (and possibly love) inhering in Mary and depending on John, as well as reciprocal ones inhering in John - there is only one truthmaking quality inhering in something external to John, and existentially depending on it. This is the case of so-called Cambridge properties [5], like being loved by Mary.

- seems plausible to assume that a descriptive property may hold for an object x in virtue of a quality inhering in a proper part of x, rather than in x itself

- To include the last two cases, we refine our definition as follows: a property P is descriptive iff, for every x, P(x) holds in virtue of (at least) a quality q being existentially dependent on x.

intrinsic properties

- a property holding for x is extrinsic iff it requires the existence of something else external to x in order to hold

- Being red and being married are examples of, respectively, intrinsic descriptive and extrinsic descriptive properties

- In the former case the minimal weak TM is a non-relational quality

- t.2024.07.26.09 why non-relational? only if red isn't "something else"

- in the latter it is a relational quality

- The intrinsic/extrinsic distinction turns out to be orthogonal to the descriptive/non-descriptive one, and each of the four combinations has its own peculiarities in terms of TMs

- e.g.

- Being red and being married are examples of, respectively, intrinsic descriptive and extrinsic descriptive properties.

- In the former case the minimal weak TM is a non-relational quality

- in the latter it is a relational quality.

- Being an apple or having a nose are examples of intrinsic non-descriptive properties, whose argument coincides with the minimal weak TM

- being Italian is an extrinsic non-descriptive "historical" property, with minimal weak TM of a birth event.

- Being red and being married are examples of, respectively, intrinsic descriptive and extrinsic descriptive properties.

- e.g.

Truthmaking patterns for properties

- no reification is necessary for intrinsic non-descriptive properties (their weak TM being already present in the domain of discourse)

- extrinsic descriptive properties is very similar to that of external descriptive relations

- three broad classes of TMP:

- partial TMPs

- strong partial

- weak partial

- full TMPs, including both strong and weak TMs as well as the relationship between them

- partial TMPs

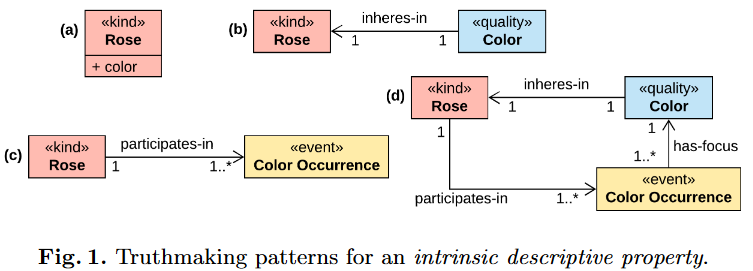

Intrinsic descriptive properties

- rarely correspond to classes, because they do not carry a principle of identity

- e.g. a rose's redness is typically expressed as a attribute-value pair within the class Rose, where the attribute name implicitly de- notes the color quality

- We have three reification options, corresponding to different TMPs:

- A weak TMP emerges when the quality is reified as a separate class

to describe the way the quality interacts with the world (Mary likes the color of this rose), or further information about the quality itself (the color of a rose is located in its corolla)- Note the 1-1 cardinality constraint, showing that a quality in- heres in exactly one object, and an object has exactly one quality of a given kind - t.2024.07.26.09 but what if the rose is partially brown? - generally more flexible, making it possible - a strong TMP emerges when the event of a "color occurrence" emerges

account for temporal information (e.g., how long the redness lasted), or for the spatiotemporal context (what happened meanwhile and where...- necessary when we need to - a full TMP, including both strong and weak TMs plus the relationship among them

- maximum expressivitiy

- A weak TMP emerges when the quality is reified as a separate class

- events can be seen as manifestations of qualities, and qualities as the focus of events.

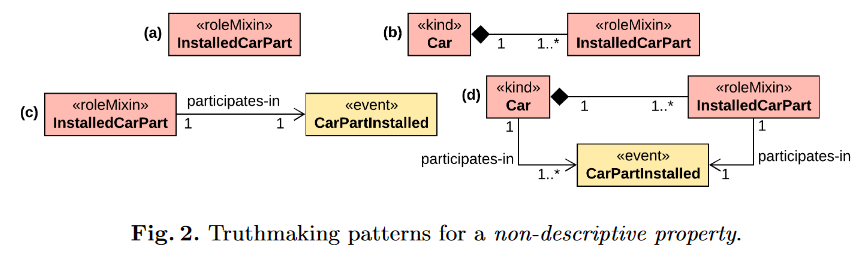

Extrinsic non-descriptive properties

- For those of them that are anti-rigid, it certainly makes sense to reify the event during which they hold, i.e., their strong TM.

- example:

- t.2024.07.26.10 the labels for b and c are mixed up.

- example:

Intrinsic non-descriptive properties

- exercise for the reader

Extrinsic descriptive

- exercise for the reader

Relations and their TMs

- In his early work, Guizzardi borrowed from [16] a crisp distinction between formal and material relations

- formal are holding between two or more entities “directly without any further intervening individual"

- ;atter requiring the existence of an intervening individual

- t.2024.07.26.10 reminds me of Are All Relations Instances of Either Material Relationship Type or Comparative Relationship Type

Backlinks