Understanding the Semantic Web through Descriptions and Situations

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/225119791_Understanding_the_Semantic_Web_through_Descriptions_and_Situations/

- topics: DOLCE DNS Ultralite

Highlights

- scalability requirements will push towards the use of automated methods to acquire, translate or merge ontologies. Such methods are known to degrade the level of formality of ontologies, resulting in the prevalence of lightweight ontologies [3]. We believe that such limitation is fundamental rather than technical; we refer the reader to the paper of Elst and Abecker for a detailed treatment of the contradiction of sharing scope, stability and formality of knowledge in information systems [4]

- Formal principles are needed to allow an explicit comparison between alternative ontologies. Exam- ples of formal principles are spatio-temporal localization, topological closure, heterogeneity of parts, dependency on the intention of agents, etc

- While formalizing the principles governing physical objects or events is (quite) straightforward, intuition comes to odds when an ontology needs to be extended with non-physical objects, such as social institutions, organizations, plans, reg- ulations, narratives, mental contents, schedules, parameters, diagnoses, etc. In fact, important fields of investigation have negated an ontological primitiveness to non-physical objects [7], because they are taken to have meaning only in combination with some other entity, i.e. their intended meaning results from a statement

- ex: a norm, a plan, or a social role are to be represented as a (set of) statement(s), not as concepts

- This position is documented by the almost exclusive attention dedicated by many important theoretical frameworks (BDI agent model, theory of trust, situation calculus, formal context analysis), to states of affairs, facts, beliefs, viewpoints, contexts, whose logical representation is set at the level of theories or models, not at the level of concepts or relations.

- On the other hand, recent work (e.g. [7]) addresses non-physical objects as first-order entities that can change, or that can be manipulated similarly to physical entities. This means that many relations and axioms that are valid for physical entities can be used for non-physical ones as well

- Interrelations between theories are notoriously difficult to be manipulated, then it would be an advantage to represent non-physical objects as instances of concepts instead of models satisfying some theory

D&S

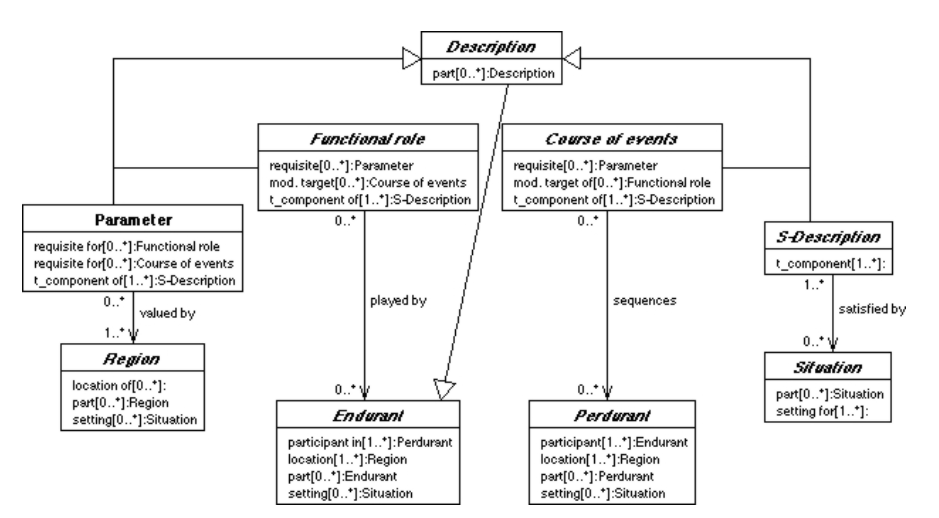

- D&S axioms try to capture the notion of “situation” as a unitarian entity out of a “state of affairs”

- A state of affairs is any non-empty set SoA of assertions a1..n that are individually coherent with the axioms in a first-order theory O, called a “ground ontology”. A SoA is a second-order entity, therefore it cannot be represented (as such) as an individual in O. Examples: a clinical data set, a set of temperatures with spatio-temporal coordinates, etc

- A description is an entity that partly represents a (possibly formalized) theory T (or one of its elements) that can be “conceived” by an agent: either human, collective, social, or artificial. A description can be an individual in O. Examples: a diagnosis, a climate change theory, etc.

- A situation is constituted by the entities and the relations among them that are mentioned in assertions a1..n from a SoA, and it is an entity in O that partly represents a (possibly formalized) model M for T, according to the axioms in O

- A situation can be an individual in O.

- a1..n must be systematically related to the components of a description in order to constitute a situation

- eg: a clinical condition, a climate change history, etc.

- Intuitively, when a description is applied to a state of affairs, some structure (a “situation”) emerges (this reflects the cognitive structuring cognitive process [6]). The emerging structure is not necessarily equivalent to the actual structure

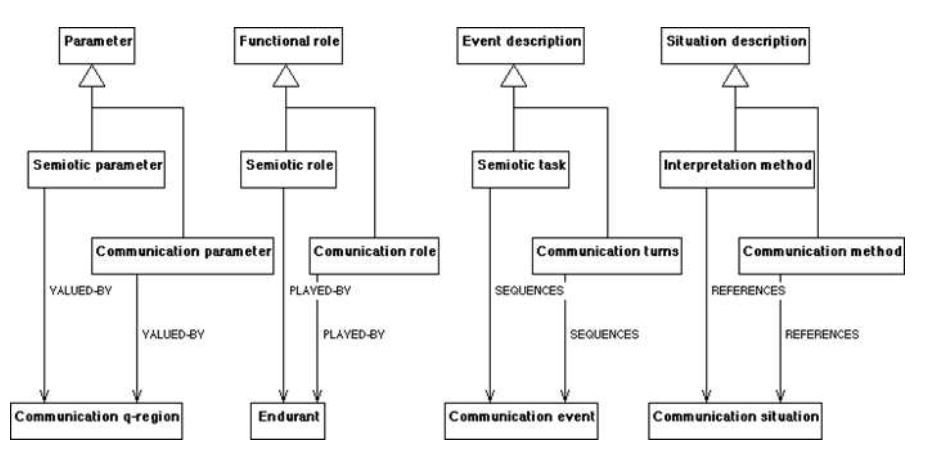

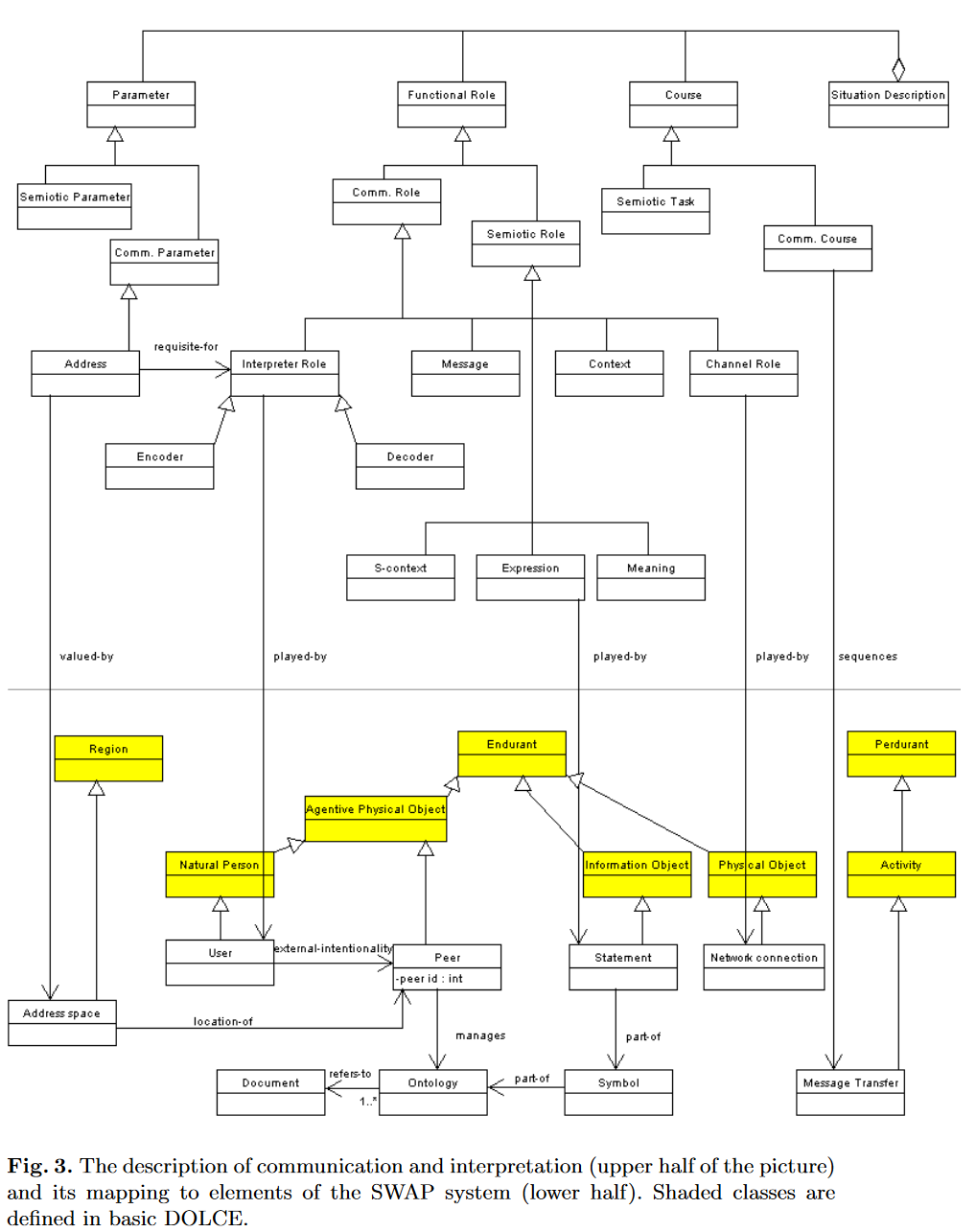

Communication

- The generic schema for our communication ontology combines two skeletal descriptions as shown in Figure 2. The description for communication consists of communication parameters valued by communication regions, communication roles played by endurants and communication turns that sequence a communi- cation event according to some method of communication. The description for interpretation concerns semiotic parameters, roles and semiotic tasks according to some interpretation method

Web's Identity Crisis

- resulted from the vague definition of Universal Resource Identifiers (URI). In practice, symbols of Semantic Web ontologies are often used to denote documents, in other cases documents containing definitions of concepts or the concepts themselves. A further difficulty with the URIs of the last type is that they cannot be denoted (resolved) by machines

Jakobson's Model of Communication

- all acts of communication are contingent on six constituent elements [13]

- the addresser or encoder [speaker, author]

- a message [the verbal act, the signifier)

- the addressee or decoder

- context (a referent, the signified)

- a code (shared mode of discourse, shared language)

- a contact or channel.

- Using the ontology of descriptions, all six constituents are modelled as functional roles: the encoder and decoder are agentive roles, while the other elements of theory are non-agentive functional roles. The method of communication is represented as a course.

Backlinks