Modular Ontology Modeling

Abstract

Reusing ontologies for new purposes, or adapting them to new use-cases, is frequently difficult. In our experiences, we have found this to be the case for several reasons: (i) differing representational granularity in ontologies and in use-cases, (ii) lacking conceptual clarity in potentially reusable ontologies, (iii) lack and difficulty of adherence to good modeling principles, and (iv) a lack of reuse emphasis and process support available in ontology engineering tooling. In order to address these concerns, we have developed the Modular Ontology Modeling (MOMo) methodology, and its supporting tooling infrastructure, CoModIDE (the Comprehensive Modular Ontology IDE – “commodity”). MOMo builds on the established eXtreme Design methodology, and like it emphasizes modular development and design pattern reuse; but crucially adds the extensive use of graphical schema diagrams, and tooling that support them, as vehicles for knowledge elicitation from experts. In this paper, we present the MOMo workflow in detail, and describe several useful resources for executing it. In particular, we provide a thorough and rigorous evaluation of CoModIDE in its role of supporting the MOMo methodology’s graphical modeling paradigm. We find that CoModIDE significantly improves approachability of such a paradigm, and that it displays a high usability.

Highlights

Introduction

- it is often much easier to develop a new ontology from scratch, than it is to try to re-use and adapt an existing ontology.

- four of the major issues preventing wide-spread re-use are (i) differing representational granularity, (ii) lack of conceptual clarity in many ontologies, (iii) lack and difficulty of adherence to established good modeling principles, and (iv) lack of re-use emphasis and process support in available ontology engineering tooling.

- If a use case requires fine-granularity data, a coarse-grained ontology is essentially useless. On the other hand, using a fine-grained ontology for a use case that requires only coarse granularity data is unwieldy due to (possibly massively) increased size of ontology and data graph.

- Even simple cases, such as the recommendation to not have perdurants and endurants together in subclass relationships

- “good modeling” appears to largely be a function of modeling experience and more of an art, than a science, which has not been condensed well enough into tangible insights that can easily be written up in a tutorial or textbook.

- Once a reusable ontology resource has been located, a suitable reuse method must first be selected; e.g., cloning the entire design into the target ontology/namespace, using owl:imports to include the entire source ontology as-is, cloning individual definitions, locally subsuming or aligning to remote ontology entities, etc.

- through ontology re-use, the ontologist commits to a design and logic built by a third party.

- keeping track of the provenance of re-used ontological resources and their locally instantiated representations may become important,

- This is particularly important in case remote resources are reused directly rather than through cloning into a local representation (e.g., using owl:imports or through alignments to remote entities using subclass or equivalence relations);

- The notion of module has taken on a variety of meanings in the Semantic Web community [2,18,60]. For our purposes, a module is a part of the ontology (i.e., a subset of the ontology axioms) which captures a key notion together with its key attributes. For example, an event module may contain, other than an Event class, also relations and classes designed for the representation of the event’s place, time, and participants.

- A module is thus as much a technical entity, in the sense of a defined part of an ontology, as well as a conceptual entity, in the sense that it should encompass different classes (and relationships between them) which “naturally” (from the perspective of domain experts) belong together.

- Modules may overlap. They may be nested. They provide an organization of an ontology as an interconnected collection of modules, each of which resonates with the corresponding part of domain conceptualization by the experts.

- modules make it possible to approach ontology modeling in a divide-and-conquer fashion; first, by modeling one module at a time, and then connecting them

- The systematic use of ontology design patterns [8,17] is another central aspect of our approach, as many of their promises resonate with the issues that our approach is addressing [28].

Related Work

- The Methontology methodology is presented by Férnandez et al. in [15]. It is one of the earlier attempts to develop a development method specifically for ontology engineering processes

- The On-To-Knowledge Methodology (OTKM) [61] is, similarly to METHONTOLOGY, a methodology for ontology engineering that covers the big steps, but leaves out the detailed specifics.

- Distributed Engineering of Ontologies Diligent, by Pinto et al. [43], is an abbreviation for Distributed, Loosely-Controlled and Evolving Engineering of Ontologies, and is a method aimed at guiding ontology engineering processes in a distributed Semantic Web setting

- In all three of these well-established methods, the process steps that are defined are rather coarse-grained. They give guidance on overall activities that need to be performed in constructing an ontology, but more fine-grained guidance (e.g., how to solve common modeling problems, how to represent particular designs on concept or axiom level, or how to work around limitations in the representation language) is not included.

Ontology Design Patterns

- Ontology Design Patterns (ODPs) were introduced at around the same time independently by Gangemi [17] and Blomqvist and Sandkuhl [8]

- Key contributions include the eXtreme Design methodology (detailed in Section 2.3) and several other pattern-based ontology engineering methods (Section 2.4). The majority of work on ODPs has been based on the use of miniature OWL ontologies as the formal pattern encoding, but there are several examples of other encodings, the most prominent of which are OPPL [14] and more recently OTTR [59].

- MOMo extends on those methods, but also incorporates results from our past work on how to document ODPs [26,29,32], how to implement ODP support tooling [22] and how to instantiate patterns into modules by “stamping out copies” [24].

- Samod Methodology [42], or Simplified Agile Methodology for Ontology Development, is a recently developed methodology that builds on and borrows from test-driven and agile methods (in particular eXtreme Design). SAMOD emphasises the use of tests to confirm that the developed ontology is consistent with requirements, and prescribes that the developer construct three types of such tests: model tests, data tests, and query tests.

Graphical Conceptual Modeling

- CoModIDE has taken influence from Vowl, e.g., in how we render datatype nodes. However, in a collaborative editing environment in which the graphical layout of nodes and edges needs to remain consistent for all users, and relatively stable over time, we find the force-directed graph structure (which changes continuously as entities are added/removed) to be unsuitable.

- the commercial offering Grafo55 offers a very attractive feature set, combining the usability of a VOWL-like notation with stable positioning, and collaborative editing features. Crucially, however, Grafo does not support pattern-based modular modeling or import statements, and only supports RDFS semantics, and as a web-hosted service, does not allow for customizations or plugins that would support such a modeling paradigm.

- CoModIDE is partially based on the Protégé plugin , as presented in [47]. OWLAx plugin supports one-way translation from graphical schema diagrams drawn by the user, into OWL ontology classes and properties; however, it does not render such constructs back into a graphical form. There is thus no way of continually maintaining and developing an ontology using only OWLAx. There is also no support for design pattern re-use in this tool.

3 The modular ontology modeling methodology (MOMo)

3.3 OWL axioms

axiomatizations can have different interpretations, and while they can, for example, be used for performing deductive reasoning, this is not their main role as part of the MOMo approach. Rather, for our purposes axioms serve to disambiguate meaning, for a human user of the ontology.

3.6.6.Set up documentation and determine axioms for each module

- Since the documentation is meant for human consumption, we prefer to use a concise formal representation of axioms, usually using description logic syntax or rules, together with an additional listing of the axioms in a natural language representation.

- In our experience, using axioms that only contain two classes and one property suffices to express an overwhelming majority of the desired logical theory [12]. We are thus utilizing the relatively short list of 17 axiom patterns that was determined for support in the OWLAx Protégé plug-in [47] and that can also be found discussed in [56].

- We would like to mention, in particular, two types of axioms that we found very helpful. One of them are structural tautologies which we have already discussed in Section 3.3. The other are scoped domain (respectively, range) axioms (introduced as the class-oriented strategy in [21]).

- As such, we recommend a rather complete axiomatization, as long as it does not force an overly specific reading on the ontology. We usually use the checklist from the OWLAx tool [47] to axiomatize with simple axioms. More complex axioms, in particular those that span more than two nodes in a diagram, can be added conventionally or by means of the ROWLTab Protégé plug-in [45,46]. We also utilize what we call structural tautologies which are axioms that are in fact tautologies such as A⊑⩾0R.B, to indicate that individuals in classes A and B may have an R relation between them, and that this would be a typical usage of the property R.88

Example modular ontologies

Highly spatial data

It is frequently common to model data that has a strong spatial dimension. The challenges that accompany this are unfortunately myriad. In the GeoLink Modular Ontology [34] we utilize the Semantic Trajectory pattern to model discrete representations of continuous spatial movement. Ongoing work regarding the integration of multiple datasets (e.g., NOAA storm data, USGS earthquake data, and FEMA disaster declarations)1717 while using their spatial data as the dimension of integration can be found online.1818 The RealEstateCore Ontology [20,25] provides a set of patterns and modules for the integration of spatial footprints and structures in a real estate property with sensors and other devices present on the Internet of Things. Elusive ground truth

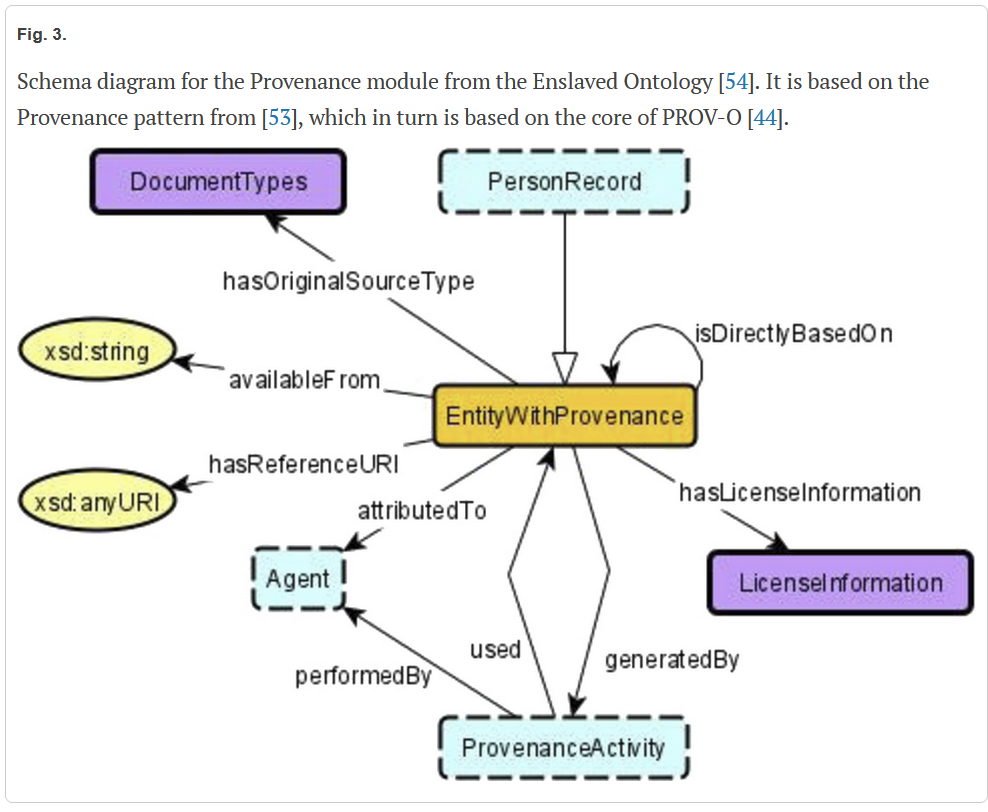

Sometimes, it is necessary to model data where it is not known if it is true, or that it is necessary to knowingly ingest possibly contradictory knowledge. In this case, we suggest a records-based approach, with a strong emphasis on the first-class modeling of provenance. That is, knowledge or data is not modeled directly, but instead we model a container for the data, which is then strongly connected to its provenance. An example of this approach can be found in the Enslaved Ontology [54], where historical data may contradict or conflict with itself, based on the interpretations of different historians. Rule-based knowledge

In some cases, it may be necessary to directly encode rules or conditional data, such as attempting to describe the action-response mechanisms when reacting to an event. The methods for doing so, and the modules therein associated, can be found in the Modular Ontology for Space Weather Research [57] and in the Domain Ontology for Task Instructions [13]. Shortcuts & views

Shortcuts and Views are used to manage complexity between rich and detailed ontological truthiness and convenience for data providers, publishers, and consumers. That is, it is frequently desirable to have high fidelity in the underlying knowledge model, which may result in a model that is confusing or unintuitive to the non-ontologist. As such, shortcuts can be used to simplify navigation or publishing according to the model. These shortcuts would also be formally described allowing for a navigation between levels of abstraction. A full examination of these constructs is out of scope, but examples of shortcuts and views, alongside their use, can be found in the Geolink Modular Ontology [34], the tutorial for modeling Chess Game Data [35], and in the Enslaved Ontology [54].

References

Backlinks